When Thistle sold Harry Milne in the transfer window - ahead of his contract expiring in the summer and probably losing him for no compensation - there was a lot of discussion about what it said about the club leadership’s view of the remainder of the season. Was the money we got by selling him six months ahead of when we would lose him anyway worth the tradeoff; the risk of not holding onto fourth position with its associated prize money we’d budgeted on?

Was selling Milne a sign of ‘giving up’ on the season, or a calculated risk to maximise the value of a player?

It’s the philosophy that teams like Brentford have lived by for years. Every player has his value. What he does for you on the pitch, moving you up the table and garnering your more prize money at the end of the season, needs to be balanced against how much another club is willing to pay (and how much you’re paying the player in salary).

It’s not just about the goals the player scores. It’s about how valuable a player’s contributions are. Does he turn draws into wins and losses into draws? And do those additional points he earns you translate to more money than a rival team is willing to pay?

Brentford famously have a player valuation model - if they’ve got a realistic chance of moving up and gaining more income with a player in the squad, they value him higher according to that financial upside. When the chance to move up is more distant, or they can get a large fraction of the same benefit from someone else in the squad (Hogan was replace, then Watkins, and Maupay, and Toney and…1), they are willing to drop the valuation somewhat. Every player has his value, and if someone offers you more for him now than you believe he contributes to the squad (and the club overall), then sell, sell, sell. It’s the flip side of buying undervalued players.

A few weeks ago, I posted about players who made the biggest impact on their team’s goal difference. The ultimate goal is to have a single metric that captures a player’s contribution to his team, because no stat on its own is enough to tell you how valuable a player is. Just looking at goals scored or chances created or shots saved is too myopic. Most stats only allow you to compare similar players (keeper to keeper or forward to forward).

But how do you judge if it’s more important to have the best goalkeeper in the division or a great winger? At some point, teams at our level will have to sell our best players - so how do we know the value of a player?

Which brings us to WAR.

Wins Above Replacement players

Wins Above Replacement is a well-trodden concept in American sports (especially baseball2,3). The idea goes like this:

A player has an impact on his team’s performance (in baseball, this might be runs batted in, or player outs and runs allowed by a pitcher)

If you remove that player and replace him with a reasonably accessible replacement player (not an identical one, but one you could reasonable source without having a superstar languishing around on the sidelines), how different would the impact be? Would you score fewer runs? Allow the opposition to get to home plate more often? And how big would the change be?

Over time, that change in impact adds up. Losing a run a game (in baseball) might not change the outcome of every game. But if you’re a run worse off on average every game, eventually there will be a game you should have won that you draw or lose. Over a season, it adds up.

So a valuable player who has an above average impact on his team, and who plays a lot of minutes, effectively adds a certain number of wins over the season. They contribute W(ins) A(bove) a R(eplacement) player.

I decided I wanted to build an equivalent for the Scottish Championship; a single number to estimate the value of a player to his team.

Which players effectively make their team more winningy4?

I started with the Goal Difference Impact from my previous post and built on it.

Each player already has a ‘Goal Difference plus/minus per 90 minutes’ (that’s what I posted about before) - how much better the team’s GD is per 90 mins when he’s playing versus when he’s not.

I then classified which area of the pitch players spent most time in games they played (Keeper, wide defensive, central defensive, central midfield, wide midfield and attack, or central forward), and gave the player a % for how much of the season they’d spent in each area (there’s no point in replacing a keeper with an average player because a keeper’s impact is different from a winger’s)

For each positional area, I calculated the ‘replacement value’ for goal difference impact - this is the level of goal difference impact of a player who is at the 25th percentile5. Basically, your replacement player would be ok but not great (which is realistic because very few teams have a perfect alternative for every player … especially the stars)

Each player then gets a ‘replacement player change’ - how much better (or worse) they are than this replacement player for each of the possible positions

The overall goal difference improvement the player produces is this replacement player change multiplied by the number of 90 minutes they’ve played at that position (so if they’ve spent 50% in central midfield, 25% as a winger and 25% at centre forward, they get compared to CM replacement players for 50% of their minutes, winger replacements for 25% and so on)

I then sum up the impact a player has had across all positions over the season

Conventional wisdom is that every 7 goals gained is equivalent to a win added. Which gives us a number of wins added by each player

So a player who plays a lot of minutes, and who maintains a high goal difference impact over those minutes, will get a high WAR. If he has a high impact over relatively few minutes (think ‘super sub’) he’ll have a modestly good WAR.

Across the division, this chart shows who has contributed the most wins to their team.

Ryan Mullen (I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again - big fan) is worth 6 wins this season to Morton.

The top 8 players are all from Morton or Ayr - which tells you that they have very impressive starters, but their in-house replacements … not great. Which is a story of its own (just not this particular story).

Four Thistle players make the top 30. Brian Graham is highest with 3.83 wins added over a replacement player (not too shabby - and what you’d expect from his goal rate). Myles Roberts, predictably, also added more than three and a half wins, even in only half a season. Neither Graham nor Roberts are easily replaced.

Banzo added 2.77 wins. And rounding out the top 30 … is Robbie Crawford.

Which isn’t quite what you’d expect. On this week’s Draw, Lose or Draw pod, Matt asked me about Crawford’s contribution (particularly under the new regime). My sense has always been that he does a lot of running, but other than that, I can’t quite put my finger on it. My general answer was: his defensive output is pretty good.

But looking at WAR (I really need a good name), he’s one of the 30 most valuable players in the division. Replacing him with a normal midfielder from the league, and we’d be 7 or 8 points worse off … and out of the playoffs.

He’s had more impact than Milne, more than Logan Chalmers, more than O’Reilly and Ashcroft … at least by this metric.

So what does he do?

Crawford’s contribution

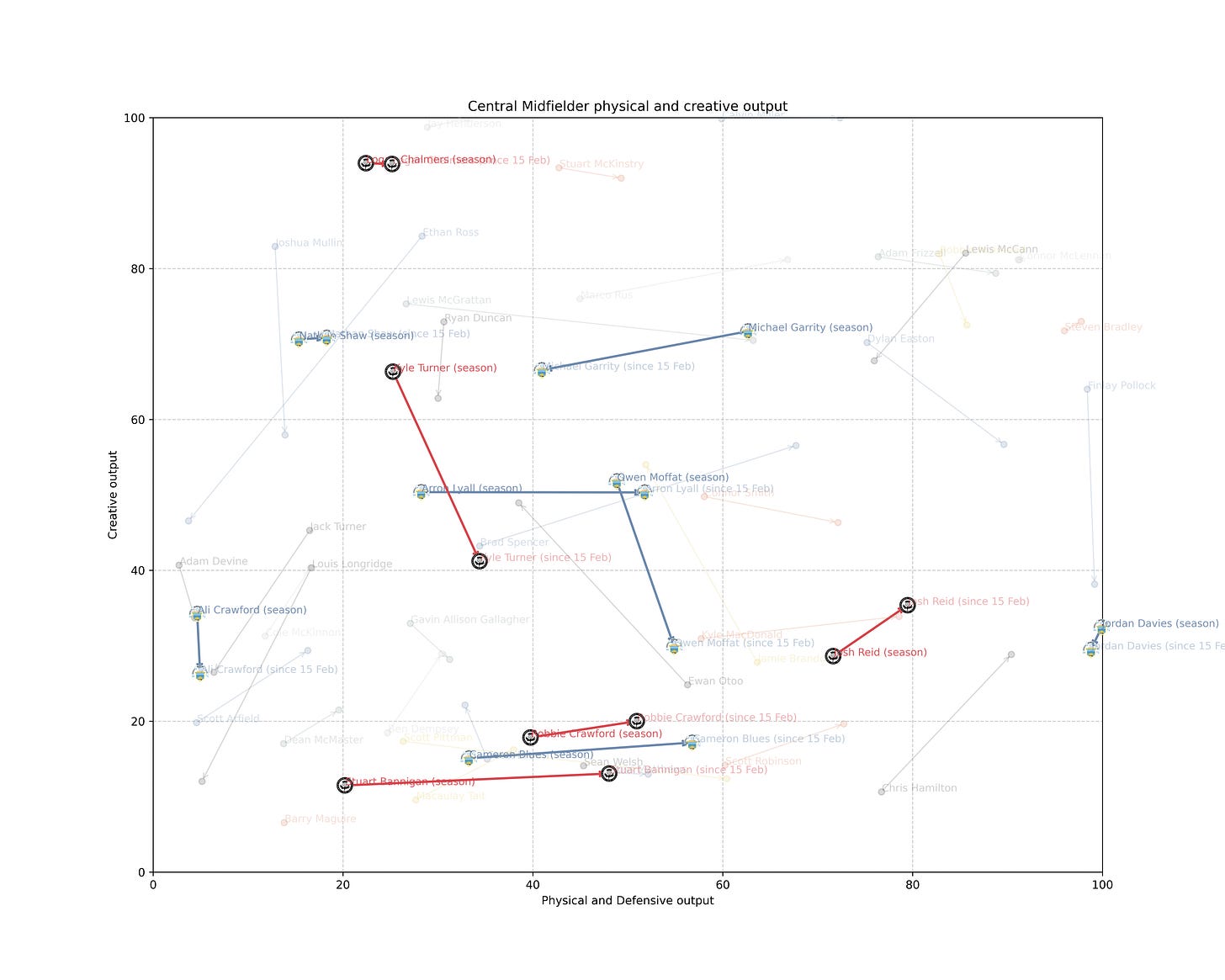

Taking inspiration from Spencer Mossman, who had a great post this week about ‘acceptable defensive contributions’ by midfielders, I decided to try his methodology out on Championship midfielders. Basically, his point was: a midfielder can get away with low creative contributions if their physical and defensive output is significant enough (and the same the other way around).

I won’t bore you with the details of the calculation, but the chart above takes loads of different measures and collapses them down to a single number for ‘defensive and physical contributions’ (duels, interceptions, successful tackles, winning the ball in the air and so on), and a single number for creative contributions (creating shots, successfully beating their man and so on).

Top left are creative machines but low physical output (hello, Logan). Bottom left are low creativity, but high defensive and physical machines (G’day Banzo). Top right are double threats. Over the season, Garrity at Morton has contributed well in both ways, for example.

Crawford, over the season, has been pretty impressive physically. He successfully tackles more than almost anyone else in the division (he’s 3 or 4 in the rankings, just behind Scott Martin). He gets into a lot of duels, presses his opponents well and generally has some lung busting output that’s not just about running, but tangibly disrupts the opposition.

Since Graham and Wilson took over (the end of the arrow in the chart), his defensive and physical output has gone up noticeably (as has Banzo’s), alongside a modest climb in creative contributions for both.

Crawford is comfortably top half across all types of defensive and physical output of Championship midfielders.

In the same period, Chalmers has basically stayed the same (with a very small lift in physical production), and Turner’s physical increase has come at the cost of a noticeable drop-off in creativity.

Josh Reid appears in the chart because he ends up pretty advanced as our left wing back.

Putting it all together

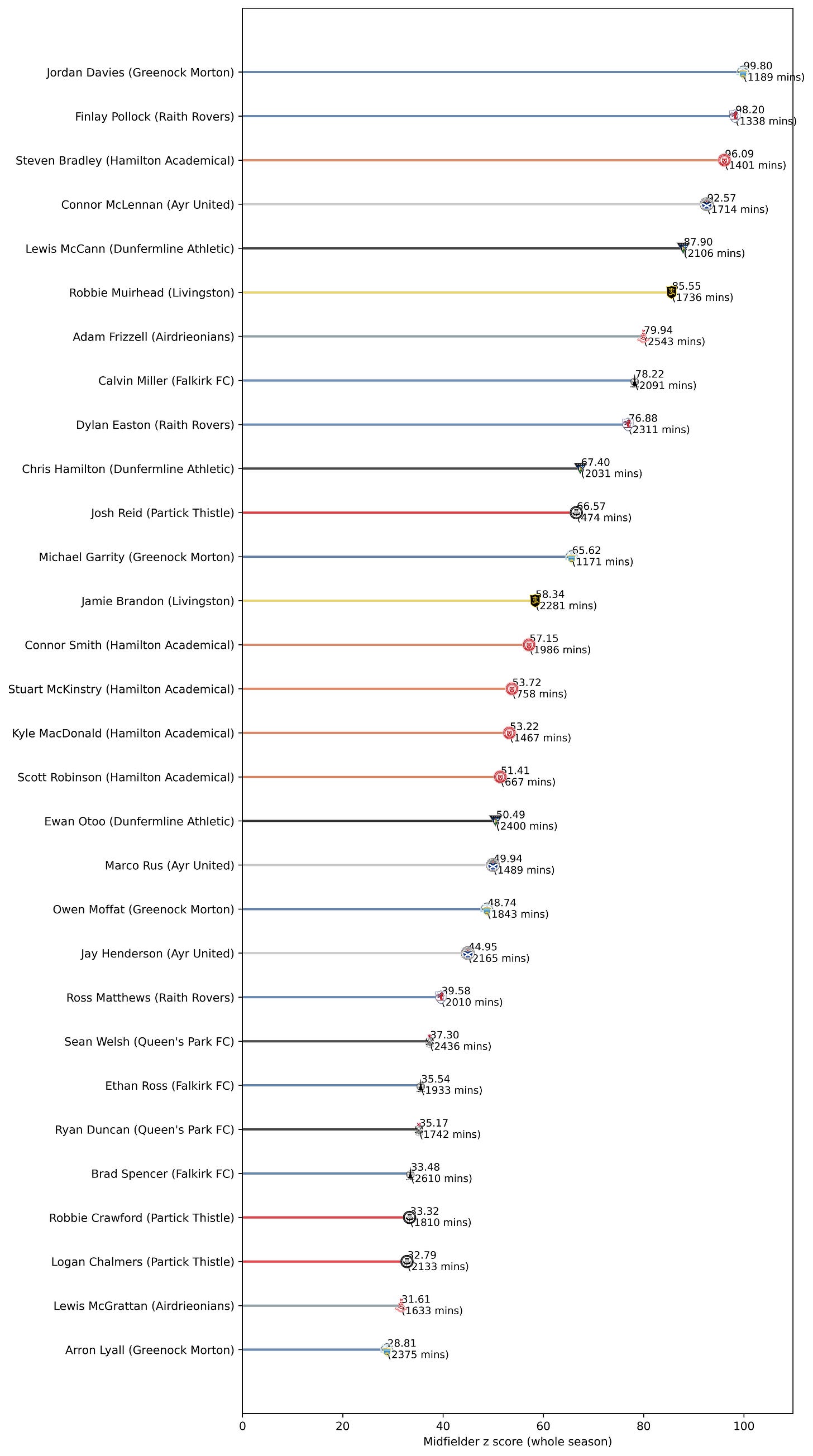

The z-score approach I used (Marc Lambers has a great post describing the background if you’re interested) wraps together loads of stats into a single number. So, having done the analysis by type of midfield contribution, I decided to end with a single number wrapping the whole 'midfielder’ contribution together.

The chart above shows a single ‘z score’ for all physical, defensive and creative impact midfielders might have. It’s pretty abstract, but helps describe how much better the best players are. It’s another tool in describing how valuable a player is - you can get a good score by contributing loads defensively or by contributing loads creatively, but really special players do both.

A few odd players make it in here because of how I’ve classified the positions - these players needed to have spent at least half their games averaging in the midfield position. So a striker who drops deep, a winger who cuts inside a lot, or a defender who pushes up might (and does!) appear.

Jordan Davies and Finlay Pollock sneak in here because they drop quite deep. Josh Reid gets in there, too as he cuts inside and plays much further forward than a traditional left back.

For now, the one we’re interested in is Robbie Crawford, who gets a 33 for his whole season contribution - just in the top 30, and basically like a Bizarro World Logan Chalmers. But what happened when Graham and Wilson took over and pushed him further forward?

This chart shows just the games played since the managerial change at Thistle. Crawford’s midfielder score has gone up by about 30% (to 42). His increase in physical contribution pushes him further up the list and increases his ‘midfield contribution’ overall quite significantly.

The new role means he contributes a lot more to what we do. Over a season, this is likely to require very high reserves of stamina, but he’s producing midfield things much more effectively - a bit more creatively, and a lot more physically.

In the same period, several Morton players have dropped off - Garrity has gone from 66 to 44, for instance. Crawford’s overall contribution in the last few games has become very similar to Garrity’s. Moffat’s physicality has gone up a bit, and his creativity has dropped almost as much as Turner’s has. Lyall, though, is contributing more defensively, and about the same creatively, so his overall score has almost doubled form 28 to 50. Which is worth watching on Saturday.

So what is it good for?

All of this isn’t conclusive.

But I think Crawford is an interesting case study. He doesn’t do any one thing that’s spectacular. Or the stuff that normally wins fans’ hearts.

He doesn’t contribute the comedy yellow cards and passpasspasspass that you get with Banzo. Or the flashes of heart-stopping creative genius of Chalmers. He doesn’t run the ball the way that Fitzy at his best does, or progress the ball like Doc did, or Lawless before the injury.

But he adds wins.

Crawford is a top thirty player in the league when it comes to wins added to his team. And he’s top thirty midfielder for his overall physical, defensive and creative production. And he’s got 30% more productive (mostly defensively, even though he’s in a more advanced role) since our managerial change.

I’m beginning to think about how I might quantify player value. But for now, whilst WAR may not be good for everything, Crawford is certainly good for WAR.

At the time, all of these sales looked risky. But with good recruitment and strategic planning they didn’t pose Brentford a problem. That’s the crucial thing. To run by this model, you need to plan well and have the replacement value already in place when you sell the star

Sabremetrics, the foundational concept of data use in sport, transformed how things worked well before Brad Pitt got involved in the Oakland As

See https://www.espn.com/mlb/war/leaders for the current leaders in this ranking

I need a good name for this metric - suggestions on the back of tenner gratefully received.

A player at this level is more likely to be available if you needed to replace your player. You’re unlikely either to have in the squad, or be able to sign at short notice, someone as good as a good player when you need to replace them. The 25th percentile means a player is better than 25% of all players at that position and worse than 75%.