Sometimes when you’re looking at data, you’re interested in patterns and clusters - things that group together in order to describe the norm or a trend. Sometimes, you’re interested in outliers - one of these things is not like the other. It’s reassuring to look at a dataset and find things that you expect to see - Erling Haaland scores a lot of goals, the pope is a catholic, that sort of thing.

What’s really fun, though, is when most of the dataset is reassuringly familiar, but one or two aspects take you by surprise.

Here’s where we’re going today: sometimes goalkeepers make your attack a lot better.

Sometimes, forwards make your defence better.

Huh.

Odd.

Spencer Mossman on Twitter gave a good example of the ‘hmm that doesn’t make sense’ effect I’m talking about this week:

Most of the data is spread in a thin band, but one player is waaaaaaay out on his own this year. Normally that means a player who is very good or very bad … but in this case, it means both. It makes no sense. The player is having the best season in one metric across all goalkeepers in the last almost-decade … and is barely cracking the top 1,000 for the second metric.

Weird.

So this week, I’ve been considering Things That Don’t Immediately Make Sense.

A couple of months back, I looked into the impact players have on their team performance. At the time, I was trying to track the impact Stuart Bannigan had on Thistle’s performance. I decided it was time to standarise the code a bit and make it more reusable in case it was useful for some other analysis.

The idea is borrowed from NBA analysis, where concepts like RAPTOR and PER codify the concept, and are quite familiar to fans. What is the difference in a team’s box score when a player is on the pitch versus when they’re not. Some players lift a team’s defence, some a team’s attack, some both. Sometimes you bring a player on who cares not a fig for tracking back, but creates chances. Sometimes you want to lock down at the expense of zero attacking threat.

I’ve built a pretty simple model at this point (models like RAPTOR go a step further and replace players with a notional ‘average’ replacement player. I’ve not done that…yet). When players are on the pitch, what is the rate of Goals Scored per 90 minutes played of their team? And what is the rate of Goals Conceded per 90 minutes played?

And what is the team’s goal scored and goal conceded rate when the player isn’t on the pitch?

How much better or worse is a team with and without a particular player.

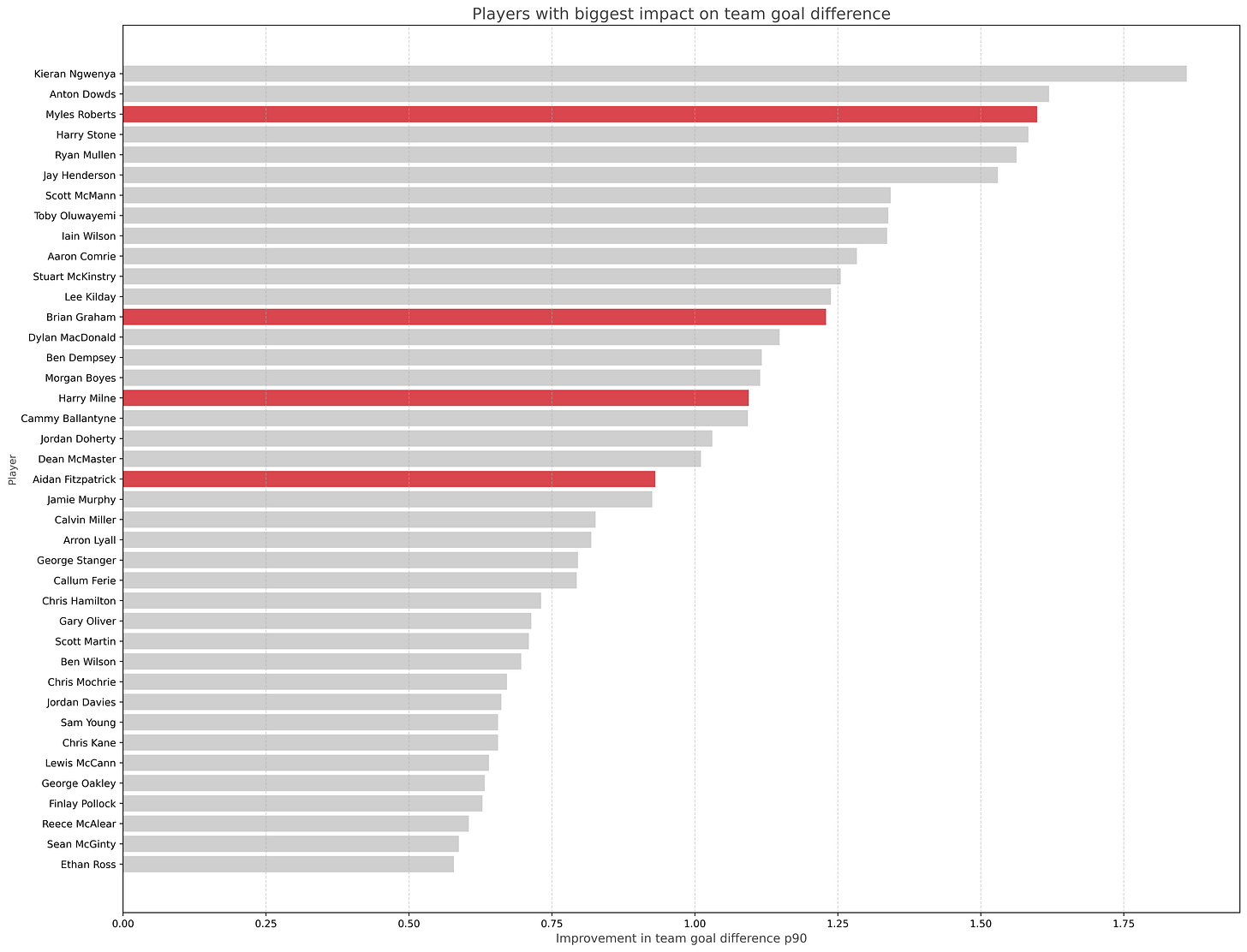

I subset to players with at least 400 minutes played to remove some small sample size players whose numbers are extreme.

The result is the bar chart further up the page.

Kieran Ngwenya leads the way - he’s logged about 1,700 minutes this year for Dunfermline, and been off the pitch for about 650 minutes. On average, Dunfermline’s GD is about 1.9 goals per 90 with him on the pitch than they are without him. Great work. He’s only been involved directly in around 4% of their goals (per Transfermarkt), but only 2 of their goals have been scored when he wasn’t on the pitch. Shame he wasn’t quite so impactful last season, but still.

Anton Dowds is also pretty high - since he’s been injured, Ayr have been about 1.62 goals per game worse off in terms of goal difference … which is pretty scary given where they are in the table. Shame he wasn’t quite so impactful when he was with us, but still. (anyone sensing a pattern yet?)

Then come a run of keepers - Myles Roberts (sigh), who presided over such a strong stretch of form, Harry Stone and Ryan Mullen (who I’m a big fan of). I mean, three of the top three are players who played for Thistle at one point, but don’t right now. Surely we can take some sort of credit?

Four Thistle players are in the top 30 - unfortunately two who are no longer with us (Myles and Milne), plus Captain-Interim-Comanager-Top-scorer-Women’s-team-mananger combo Brian Graham and Aidan Fitzpatrick.

I started to dig into what impact these players have had - one might assume that keepers have a good impact because they improve the goals conceded count, but have zero impact on the other side of the ball. But it’s worth finding out.

There are (roughly) four groups in this chart when you look at the top 40 players by overall goal difference impact:

“Turbo Defence” - Those that improve the defence with negligible impact on goals scored (i.e. near the zero line top-to-bottom, but quite far left). You’d expect most goalies to be here.

“Cautious Attackers” - Those that have a (slight) net improvement in goals conceded, but a big positive impact on goals scored (high up the chart and just to the left of the zero line left-to-right)

“Carefree Attackers” - Those that cause a (slight) degradation in the defensive side (the team concede more goals with them in the team), but generate a lot more goals scored when they are in the team - you’d expect quite a lot of strikers who don’t get involved in tracking back here.

“Double Threats” - Those who improve both the goals conceded rate and goals scored rate by a noticeable amount. These are likely to be a team’s key players, probably midfield generals, high assist players and so on.

Turbo Defenders on the Wing

Thistle dominate the first group - we have three players in the ‘Turbo Defence’ area … though unfortunately, two of them are Myles and Milne.

Surprise number 1: Aidan Fitzpatrick makes our defence better when he’s on the pitch.

Which is not what you’d expect, if you were to listen to some Thistle fans, who want him to work harder, press more, and all the rest. We concede something like 0.75 fewer goals per game when Fitzy plays. Which is A Good Thing.

Keepers who improve the front line

As I said before, there are several keepers in the list. What’s interesting is that while both Mullen and Stone improve their team’s goal conceded rate when they’re on the pitch (by 0.6 and 0.4 goals per game respectively … considerably lower than Myles Roberts’ 1.5), they also seem to improve the team’s goal scored rate (by 1.0 and 1.1 goals per game respectively).

I suspect what’s happening here is that when a good goalkeeper is in the team, the players in front of him are more confident, and are more willing to take attacking risks - fullbacks can push forward, midfield can advance more, knowing that the guy at the back will mind the store. Good keepers also often improve defensive structure, which helps buildup from the back.

Surprise number 2: The psychological effect of a good keeper on the whole team’s attacking production is significant.

Ferrie at QP is even more stark. He basically has zero impact on the goals conceded rate … but his team score around 0.8 goals per game more with him in nets.

Huh.

Odd.

Forwards who make the defence better

The flip is also true. Jay Henderson has been generating all sorts of headlines during his loan spell in the Championship, hitting something like a goal involvement every game recently.

And he sits firmly in the ‘double threat’ zone. He obviously improves his team’s attack - to the tune of 0.7 goals p90. But even more pronounced is his impact on the defence, with a 0.9 goals conceded p90 improvement when he’s on the pitch.

Scott McMann also improves Ayr’s attack from the defence.

Brian Graham improves our attack by 0.7 and defence by 0.5 goals p90, respectively.

Suprise number 3: outfield players often have a big impact at the ‘wrong’ end of the pitch.

So what?

You could go on with this sort of analysis.

But I think there are a few takeaways here…

Firstly, a good player impacts the whole team. Knowing you have an excellent striker means the defence feels happier doing their job - and just because they don’t track back doesn’t mean they make the defence worse. Having a winger who doesn’t add defensive actions directly can still help the team shape significantly.

Secondly, you can’t always rely on received wisdom about a player. Aidan Fitzpatrick is a surprisingly large cog in our defensive performance this year.

Thirdly, this is a useful indicator of what a team is trying to do in a given game situation (because sometimes the data tells you what you expect like a reassuring comfort toy). Robbie Crawford makes our defensive performance quite a lot better (+0.6 goals p90 improvement), but our attack a bit worse (-0.3). Oli Shaw makes Hamilton’s attack a lot better (+0.9) but the defence noticeably worse (+0.5) … particular players give a pointer to what the whole team is attempting to do (or is unconsciously doing in some cases).

Fourthly, from a recruitment point of view, I think this is a useful layer to consider. It’s not the reason we should sign a player, but it is a good reassurance. A player with a good ‘plus-minus’ score is likely to be an overall positive impact on the pitch. It also gives an indication of what we’re likely to sacrifice with a player - if we’re going all-out attack, it’s probably ok to sign a player who makes the defence a bit worse if he also makes the attack a bigger amount better. These numbers are all influenced by game state (whether you’re winning or losing), team profile, form, when players tend to be brought on, and overall playing style, and so on its own, it’s not enough. but it does help us make decisions in a bigger context. Which is something that the new Sporting Director can help us decide.

When we play QP next week, there are players who we can expect to make their defence better (MacGregor and Duncan). And players who will improve their attack (Ferrie <shrugs> and Turner). So watching those players helps us decide what they’re trying to do (ok, maybe not Ferrie, but you get the point). Who they take off or sub on helps to show how vulnerable or dangerous they are likely to be.

It’s always good to expect to be surprised when you see the data.

Postscript

Whilst I was thinking about this data this week, Disney announced it was winding down FiveThirtyEight. If you’re not familiar with it, they have pushed forward data journalism and storytelling significantly in the last 10-15 years. Their podcasts are always thought-provoking, they share the data they use so others can ‘mark their homework,’ and they tell interesting, challenging, visually pleasing and insightful stories. Recently they’ve focused on politics exclusively, but historically, they’ve told stories in other realms, including sport.

They produced the primary exemplar that inspired my BOING model, my Power Ratings, and this particular piece of analysis (Nate Silver, erstwhile founder of 538, was behind similar systems called CARMELO and RAPTOR for the NBA).

It’s a real shame it’s going away - I’ve loved their approach to telling stories. Nate Silver has launched an equivalent podcast and substack (Silver Bulletin) in recent months since he left 538, which is beginning to broaden out to cover American sports as well as politics. Galen Druke, who led the podcast for the last few years, also has a substack (GDPolitics).

I mostly just wanted to acknowledge that I’ve learned a lot from 538 over the years, and owe a lot of my approach to their ideas and inspiration. So thanks for the memories, guys, and best of luck in what you go on to.